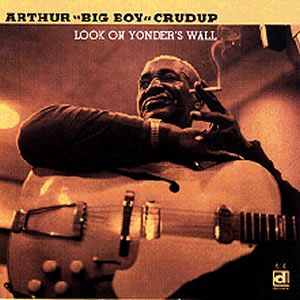

The Forgotten Bluesman: Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup

You’re never too old to do good …

Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup

You’re never too old to do good …

Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup

Through the haze and distance of history, it some times becomes far too easy to forget that so many blues players back ‘in the day’ never got their due either in the way of money or reputation. So many of the originators never earned their gain from their songs and many died destitute and forgotten. One such player, Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup who is often times referred to as the Father Of Rock and Roll, is a prime example. Some agree with that title and others do not but regardless of where you are on that particular argument; there is no denying the importance that Crudup played in the music that would come to dominate the music scene in the several decades that followed.

Crudups early life followed a familiar path when it comes to blues musicians. He was born on August 24th, 1905 in Forest, Mississippi to a rural farming family. Like so many before him, Arthur (a large child which earned him his nickname ‘Big Boy’ which he carried with him through out his life) started his musical education singing in choirs in the local church. At the age of 10, his family relocated to Indianapolis, Indiana for work. A year later they returned to south ending up again in Forest, Mississippi. The family bounced back and forth between Forest and Clarksdale through 1935 where Crudup earned his keep working farms.

In the early part of 1939 Arthur decided to pick up the guitar and taught himself the basics and began playing at local parties in and around the Clarksdale area. Later that year he joined up a gospel group, The Harmonizing Four and relocated to Chicago, Illinois where the group sang at various churches. Crudup told Rolling Stone magazine in 1971 “What started me out was getting stuck in Chicago and stranded. I was a gospel singer. And after getting stranded, why, I seen I could make a better buck signing the blues than I could in gospel songs. And I turned to the blues.”

Life wasn’t easy; he found himself living in a crate under the 39th Street El Station and playing for pennies on the street corner. A passerby stopped and invited him to play at a party. The man turned out to be blues producer Lester Melrose (a name that has become somewhat synonymous with the unscrupulous treatment of blues players in the early days) who worked for the Bluebird label. Melrose happened to manage other blues musicians of the time like Tampa Red, Bukka White, Roosevelt Sykes and Big Bill Broonzy.

And like the others under Melrose’s control, Crudup fared no better. During his time with Melrose, Arthur wrote a handful of songs that have become blues standards like ‘Rock Me Mama’, ‘Mean Ol’ Frisco Blues’ and ‘My Baby Left Me’ and one song in particular that very well may have primed the pump for what became rock and roll. Crudup’s song ‘That’s Allright Mama’ (which he wrote after borrowing a line from the Blind Lemon Jefferson song ‘Black Snake Moan’) was a minor hit for the struggling bluesman. But it’s what happened to the song that literally changed the music scene forever.

By 1947 Crudup realized that Melrose had been cheating him out of his royalties for the recordings he had done and he began withdrawing from music and returned south where he began to run a reasonably successful bootlegging business. But the he still dabbled; occasionally recording for RCA as well as with Ace Records, Checker and Trumpet. He still played locally and on the southern ‘Chitlin’ circuit often appearing with Elmore James and Sonny Boy Williamson. In 1954 Crudup was sitting at a bar in Forest, Mississippi when someone popped a coin in the jukebox and ‘That’s Alright Mama’ by Elvis Presley (Presley’s first hit) began to play. Crudup was incensed and wrote to Melrose asking about the royalties for the song. He never received a straight answer from Melrose. Even throughout the 60’s the most Arthur ever heard was in the way of the occasional one or three dollar check.

Crudup told Chris Holdenfield in an interview in Rolling Stone “The company paid my manager, but he didn’t pay me. I was to get 35 percent of every dollar that he received. Well, I failed to get it.” By the mid 50’s Arthur had grown completely disillusioned with the music business and simply began to fade away from the blues scene. He relocated to Virginia where he would play occasionally but worked primarily as a farm laborer (and still bootlegging moonshine to a few local drinking establishments) to augment his income. Throughout his life, Arthur supported 13 children of which only 4 were his actually his.

In 1968, Philadelphia based blues manager, photographer and advocate Dick Waterman sought out Crudup, finding the poverty stricken bluesman and began a rather stringent campaign to secure some level of royalties for him (as well as trying to coax the bluesman back into the blues music arena. For the next few years of his life, Crudup did return to a changed music scene, playing in small clubs and festivals as well as recording again. He began earning a living with his music. He toured with Bonnie Raitt as well who also became a champion for the aging bluesman.

Waterman contacted The American Guild of Artists and Composers and negotiated a small settlement for Crudup. In 1973 Waterman went after Hill and Range, the music-publishing house that ‘owned‘ the songs. In a very odd set of circumstances, according to Waterman, he and Crudup had negotiated a deal for approximately $60,000 for Crudup. When the lawyer dealing with the issue went upstairs to get the check signed by the manager, he returned to the table pale and shaken. “He won’t sign the agreement. He said it gives more away in settlement than you could hope to get from litigation.”

Waterman said in his book Between Midnight and Day, “ We were not going to get anything at all… I stood in front of Arthur and told him over and over that we would get them and make them pay for that they had done to him…Arthur looked me in the face and spoke slowly “I know you done the best you could. I respects (sic) you and I honors (sic) you in my heart. But it just ain’t meant to be.”

Crudup died the following spring, on March 28th,1974 from heart disease and complications from diabetes in Nassawadox Hospital in Northhampton, Virginia. But the story wasn’t over yet. Waterman contacted an associate with Warner Brothers (Waterman was managing Bonnie Raitt and had managed to get her signed to the label) and explained the outrage he had over how Hill and Range had gotten over on Crudup). Warner Brothers took up the cause and aided Waterman in his campaign against the publishing house. Around the same time Chappell Music was moving to buy out Hill and Range and when they discovered that there was an unresolved legal dispute over the royalties with the deceased bluesman, they refused to move on with the purchase. Finally Waterman had the leverage he needed and Hill and Range settled with Crudup’s estate. The first check they wrote was for $248,000.00 Over the course of the next thirty years, Crudups estate would earn over $3 million from owed royalties. Despite the slight righting of the scales of justice in the way of money, Crudup still never really secure the reputation he deserved.

Elvis Presley often said that Crudup was his favorite bluesman and acknowledged his debt to the man (in theory more than practice) but in the end, Crudup faded to the back pages of the blues bible and returned to the earth as a footnote. But you have to wonder how things would have gone for Elvis in those early days without ‘That’s Alright Mama’ and the bluesman with the gentle soul.

[FONT=Tahoma]"All I can do is be me ... whoever that is". Bob Dylan [/FONT]